Sugar is still in the doghouse in the nutrition world. We understand the undeniable connection of soda and sweetened beverages with obesity, especially childhood obesity. Eating a lot of refined sugary foods or drinks on a regular basis is associated with not only weight gain but type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and of course tooth decay. By now, most Americans also understand that eating cookies and sweets many times a day doesn’t make you feel good physically or mentally as it’s often accompanied by regret/guilt. But in line with extremes of American behavior, people are now demonizing fruit and even some vegetables that are “higher” in sugar. Every time I hear a patient ask me incredulously, “It’s ok to eat fruit?!” I’m just as incredulous that I have to respond in defense of fruit.

One of my favorite podcasts by Dr. Ranjan Chatterjee interviewed researcher Dr. Tommy Wood who said it best: Nothing is all good, nothing is all bad; context is always key. How often, how much, and with what else?

First, what is sugar?

Sugar or sucrose is a carbohydrate found naturally in plants. Table sugar is derived from the sugarcane plant, with the sugars being isolated and refined into what we know as white table sugar. Chemically it’s a “disaccharide” meaning two simple sugars, half fructose and half glucose joined together. In our gut, white sugar breaks down into these two simple sugars. Most carbohydrate foods with longer strings of glucose like bread, pasta and potatoes also break down into simple sugars. Fruit, another carbohydrate food, contains these simple sugars which I’ll cover later. Sugar as glucose is crucial to our survival as our most efficient energy source. But we usually eat more sugar than we need, because our food supply is overloaded with sugar. If we don’t watch carefully, we consume excess refined sugar not just from sweet treats but from cereals, granola, yogurt, protein bars, vanilla plant milks, bottled smoothies, Vitamin water (a standard 20 oz. bottle of Vitamin Water Power-C contains 32 grams added sugar!), salad dressings, BBQ sauce, etc etc. Too much sugar causes our pancreas to become stressed secreting extra insulin to shuttle sugar out of our bloodstream. Only a small amount is used for immediate energy; the rest is converted to fat.

When is sugar a problem?

Sugar can be a problem based on the type and amount you choose. Foods and drinks with a large amount of added refined sugars, often falling into the category of ultraprocessed foods, tend to be higher in calories and artificial additives/preservatives and lower in nutrients. Of course they taste great so you tend to reach for them often, but as you fill up, your intake of whole nutritious foods that your body needs goes down. Refined sweeteners also have a strong glycemic impact, which means a blood sugar surge, and the more you eat in one sitting the higher your blood sugar goes. As I noted above, this stresses your pancreas to make more insulin. Chronically elevated insulin levels is linked with inflammation and weight gain, which is why high sugar intake is strongly associated with inflammatory conditions like diabetes and heart disease. Another potential problem is that in some people regular high intakes of refined sugar foods can lead to intense cravings or addictive qualities as they may affect hormones and neurotransmitters in your brain. It’s not yet clear if it’s the refined sugar alone or the ultraprocessed food that contains it. Foods with naturally occurring sugars like fruit and dairy (containing the sugar lactose) do not have an “addictive” effect and do not cause blood sugar surges if eaten in reasonable amounts.

So should I just cut out carbs and sugar and follow a low-carb diet?

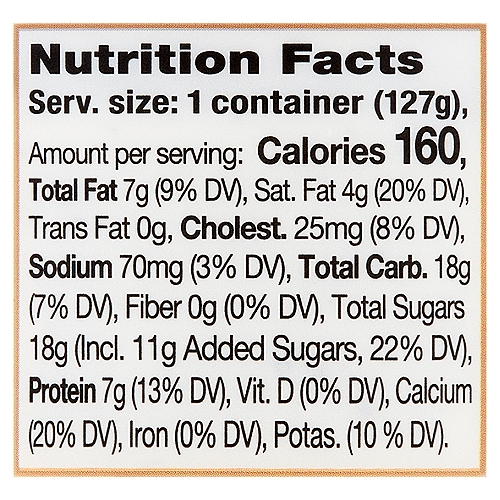

This doesn’t mean you have to avoid all refined sugar. As noted above, it’s the type and amount. I guide my patients with diabetes to look for less than 8 grams of added sugar per serving on a processed food. Keto and other very low carb (VLC) diets are popular, and fans argue that no sugars and carbs are needed because your body can convert fats and protein into glucose, but it’s a clunky process. This is confirmed by the majority of patients I see who’ve followed VLC diets whose major complaint after experiencing a short-lived energy boost is “no energy”; another complaint that prevents long-term compliance (more than one year) is intensified cravings for carbs, especially bread/potatoes/pasta. The craving could be due partly to deprivation (wanting what you can’t have) but I believe it’s also due to our bodies being designed to run on some carbohydrate. That doesn’t mean eating starch at every meal, but it could translate into a day that includes some fruit, a cup of oats, a serving of beans, a sweet potato–other types of carbs that turn into the simple sugar glucose used for energy.

What about fruit?

Fruit contains the simple sugars glucose and fructose. Fructose gets a bad rap but keep in mind it’s the ultraprocessed type of high-fructose corn syrup associated with bad health outcomes, not the naturally occuring fructose in fruit. Fruit is also a nutrient powerhouse with fiber, water, vitamins, and minerals that all digest beautifully in your gut to give you a boost of energy and the pleasure of sweetness. That said, some of my patients with diabetes who are very meticulous with their diets and use a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) report that certain fruits spike their blood sugar, such as grapes and mangoes. When this happens we look at context: what was the fruit eaten with and did their blood glucose drop back down withen the hour? Sometimes eating fruit with too many other carb foods like toast and cereal can cause a spike, so we try to reduce the total carbohydrate amount. If that wasn’t the reason, we reduce the portion of that certain fruit because there is individual variability in blood sugar responses to specific foods. Also if their glucose dropped down fairly quickly it does not concern me as much, though we don’t want to see frequent super-high surges after meals.

What about natural less-processed sweeteners?

Some of my patients swap out table sugar for “all-natural” sweeteners like honey, agave, molasses, maple syrup, coconut sugar, and date sugar. Although they undergo less processing, their simple sugar amount stays the same. Per teaspoon, these sweeteners vary slightly in sugar amount compared with table sugar; some are higher like honey and coconut sugar, and some are bit lower like date sugar. So using them if you have prediabetes or diabetes depends. If you’re putting a teaspoon in tea or plain oatmeal, that’s fine. If you’re pouring maple syrup on pancakes or oatmeal with fruit, it will likely cause a blood glucose spike. If you’re using 2 tablespoons of honey (34 grams simple sugars) in coffee or tea beause you think that is healthier than using stevia or monk fruit, I’ll tell you you’re wrong. I continually see results of patients’ CGMs who show the spikes. The impact of these sweeteners on your blood sugar is the same as refined table sugar, despite some claims they have a lower glycemic impact. But ultimately it depends on how your body processes them so if you have access to a glucometer or CGM, use them to see how your body responds to different types and amounts of sugar and sugary foods. If you exercise regularly, sleep fairly well, control stress, and generally eat high-fiber balanced meals, your body may process sugar more efficiently compared with someone who does not have these lifestyle habits.

I hope this post provides some deeper insights into sugar. As always, I welcome your comments!